Turkey has a growing population of 76.6 million inhabitants and is considered to be a large middle-income country. While it is a growing economy, it also has several social, economic and regional disparities. Turkey is also a candidate country for membership of the European Union.

Challenges and opportunities

Although there has been a steady progression of education reforms in Turkey over the last few years, many challenges still remain. The country is making great efforts to reach the five EU benchmarks: a reduction in early school leaving, participation in early childhood education and care, the completion of upper secondary education, the promotion of lifelong learning and an improvement in student performance in reading, maths and science. The overall employment rate in Turkey is also below the EU average. The educational attainment rates are below the EU average, as is the participation rate of the working population in all levels of education. These are challenging issues in light of a growing need for an internationally competitive skilled labour force in growth sectors (UIL, ETF, Cedefop, 2015).

According to the TURKSTAT figures[1], the working population’s overall educational attainment levels are low compared to the EU-28 average or that of other candidate countries: for example, 68 per cent of Turkey’s labour force consists of people with either basic education or incomplete basic education. The average number of years in education is 6.8 for males and 5.3 for females. Problems accessing education with relation to gender, rural/urban and social background (such as enrolment, dropout and graduation rates) continue to exist. EUROSTAT data for 2010 also demonstrate the high proportion (43.1 per cent) of early school leavers in Turkey compared to the average proportion of 14.1 per cent in EU-28. At the same time, Turkey faces the challenge of educational bottlenecks that hinder access to the current tertiary education system for young people, as a result of which many are compelled to join post-secondary vocational schools (MYOs), which are not sufficiently labour market-oriented. There is also a view that university graduates are preferred in the labour market, even though MYO-grads could be more useful.

National standards, policy and framework activity

To address the above challenges, Turkey promoted and developed some initiatives. One of Turkey’s aims while establishing the Turkish Qualifications Framework is to facilitate the recognition, validation and accreditation of non-formal and informal learning and to increase the participation and attainment rates, with more individuals obtaining qualifications that have an effect on their personal, educational and career development. For Turkey, recognition and validation is an important pathway to lifelong learning and a response to the many challenges its citizens face in the educational system.

The Turkish system of recognition and validation of non-formal and informal learning started development rather recently. Certificates awarded by authorized certification bodies are not considered equivalent to those acquired in formal education and do not provide access to the formal education system, but are recognized on the labour market.

In 2010, the European Union supported the strengthening of the Vocational Qualifications Authority and the National Qualifications System in Turkey by promoting lifelong learning and the recognition of the outcomes of formal, non-formal and informal vocational education and training aligned to labour market needs. It was considered important to have a sustainable National Qualifications System based on agreed occupational standards and an appropriate system of assessment and certification in alignment with all levels of the European Qualifications Framework (EQF).

A cornerstone of this development was Law 5544 in 2006, according to which the Vocational Qualifications Authority (VQA) was established as the responsible tripartite body at a national level for the validation of formal and non-formal labour market-oriented qualifications. The VQA was also deemed responsible for the implementation of the National Vocational Qualifications System based on National Occupational Standards (NOS) with a strong sector involvement and for reinforced quality assurance processes for assessment and certification. Since the establishment of VQA, over 500 NOSs, mainly between levels two and seven, have been developed and adopted as a basis for development of national vocational qualifications for validating non-formal learning through accredited and authorized certification bodies (Cedefop, 2014).

In March 2015, thirty-five accredited and authorized certification bodies were operational and it is expected that these numbers will grow (UIL, ETF, CEDEFOP, 2015). Specific occupational standards are in use within authorized certification bodies for certifying workers through validation of non-formal and informal learning. An EU grant scheme was launched to support the development of new authorized certification bodies with branches all over the country. However, at the end of 2014, the demand for certificates was not as high as expected. All the same, with the establishment of the TQF and its quality assurance functions, VQA will start authorizing training accreditation bodies, giving individual providers the accreditation needed to assess and certify workers based on occupational standards that inform national vocational qualifications. However, only VQA will be responsible for the verification of vocational qualification certificates once they have been obtained by workers.

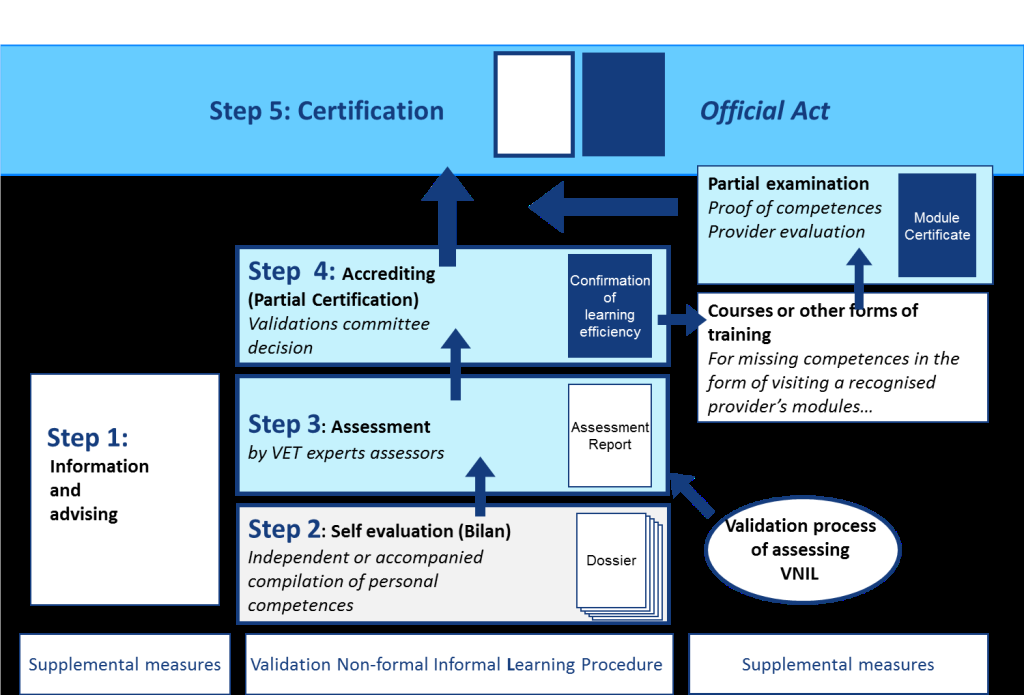

The Regulation on Vocational Qualification, Testing and Certification[2] defines the stages of the validation process as a whole. This process is valid for vocational qualifications gained through formal, non-formal or informal learning and for the recognition of prior learning. Any individual intending to certify their qualifications can apply to be tested by an authorized certification body, which in turn passes on the relevant documents to the VQA to determine eligibility. Individuals have the chance to certify their competences based on single units as well as for full qualification. The RVA practitioners are mostly teachers but their occupational profile depends on the respective sector for validation.

Furthermore, the comprehensive Turkish Qualifications Framework (TQF) continues to develop, one which will bring together different types of qualifications for general education, initial and continuing vocational education and training, adult lifelong learning and higher education, as well as qualifications gained through non-formal and informal learning. The TQF will integrate the National Vocational Qualification System (NVQS) and a qualifications framework for higher education. The Ministry of National Education will award qualifications, as an alternative to qualifications as parallel sub-frameworks. TQF supports the processes for recognition of prior learning and identifies qualification type descriptors based on learning outcomes.

The TQF will become a key instrument for the recognition and quality-assurance of lifelong learning. The learning outcomes approach is seen as an essential part of the TQF. Occupational standards should also be described in terms of learning outcomes, corresponding units and assessment criteria. The MoNE has launched a curriculum reform in secondary education for both general and vocational/technical schools. Vocational curricula are modularized and the MoNE has a database of more than 4,000 modules that are also used to certify adult learning. Additionally, there are plans to establish a national credit system for VET.

Stakeholder engagement

Apart from formal education, the Ministry of National Education (MoNE) coordinates and supervises non-formal learning activities, initiatives and projects through the Lifelong Learning Directorate General. With respect to the National Vocational Qualifications System, the VQA, which is the main responsible body at national level, brings together a wide range of stakeholders and comprises a general assembly, an executive board and service departments. The general assembly is composed of representatives from different ministries, education state institutions, employers’ organizations and labour unions. The executive board consists of elected members from the Ministry of Labour and Social Security, the Ministry of National Education, the Higher Education Council, vocational organizations, the Confederation of Trade Unions and the Confederation of Employers’ Unions. The Council of Higher Education (CoHE) is the designated committee responsible for the development and implementation of a qualifications framework for higher education.

VQA supervises validation of non-formal and informal learning through accredited certification bodies, including sector organizations, some universities, chamber affiliated centres and private companies. The accreditation of these bodies for each qualification certification is based on the ISO-17024 standard for personnel certification, implemented by the Turkish Accreditation Agency (Türkak) and authorized by VQA.

References

CEDEFOP. 2014a. European inventory on validation of non-formal and informal learning: country report Turkey. http://libserver.cedefop.europa.eu/vetelib/2014/87078_TR.pdf

CEDEFOP. 2014b. Turkey: European inventory on NQF 2014. http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/el/publications-and-resources/country-reports/turkey-european-inventory-nqf-2014

Regulation on vocational qualification, testing and certification. http://www.myk.gov.tr/images/articles/editor/SBD_EN.pdf (Accessed 5 January 2016).

UIL, European Training Foundation(ETF) and CEDEFOP. 2015. Global inventory of regional and national qualifications frameworks, v II: national and regional cases. Hamburg, UIL.

[1] https://www.devex.com/projects/grants/promoting-of-lifelong-learning-in-turkey/4489 [accessed 8.01.2016].

[2] http://www.myk.gov.tr/images/articles/editor/SBD_EN.pdf

Source: UNESCO UIL