LabourNet: Bangalore-based social enterprise

Background

India is in the process of fully operationalizing frameworks like the National Skills Qualifications Framework (NSQF) as well as tools and mechanisms for the Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL). However, in the absence of full implementation of such frameworks, local institutions have developed their own solutions to the problem of creating a meaningful certificate of learning and other challenges around implementing RPL. One such initiative for workers in the construction sector has been developed by the Bangalore-based social enterprise LabourNet (City Guilds Manipal Global, 2012).

LabourNet is an initiative of MAYA (Movement for Alternatives and Youth Awareness), a non-governmental organization based in Bangalore. LabourNet’s vision is to transform the lives of informal sector workers (93% of India’s workforce) and help them to move from poverty, deprivation, and lack of social and economic mobility, to become strong, professionally competent and empowered workers.

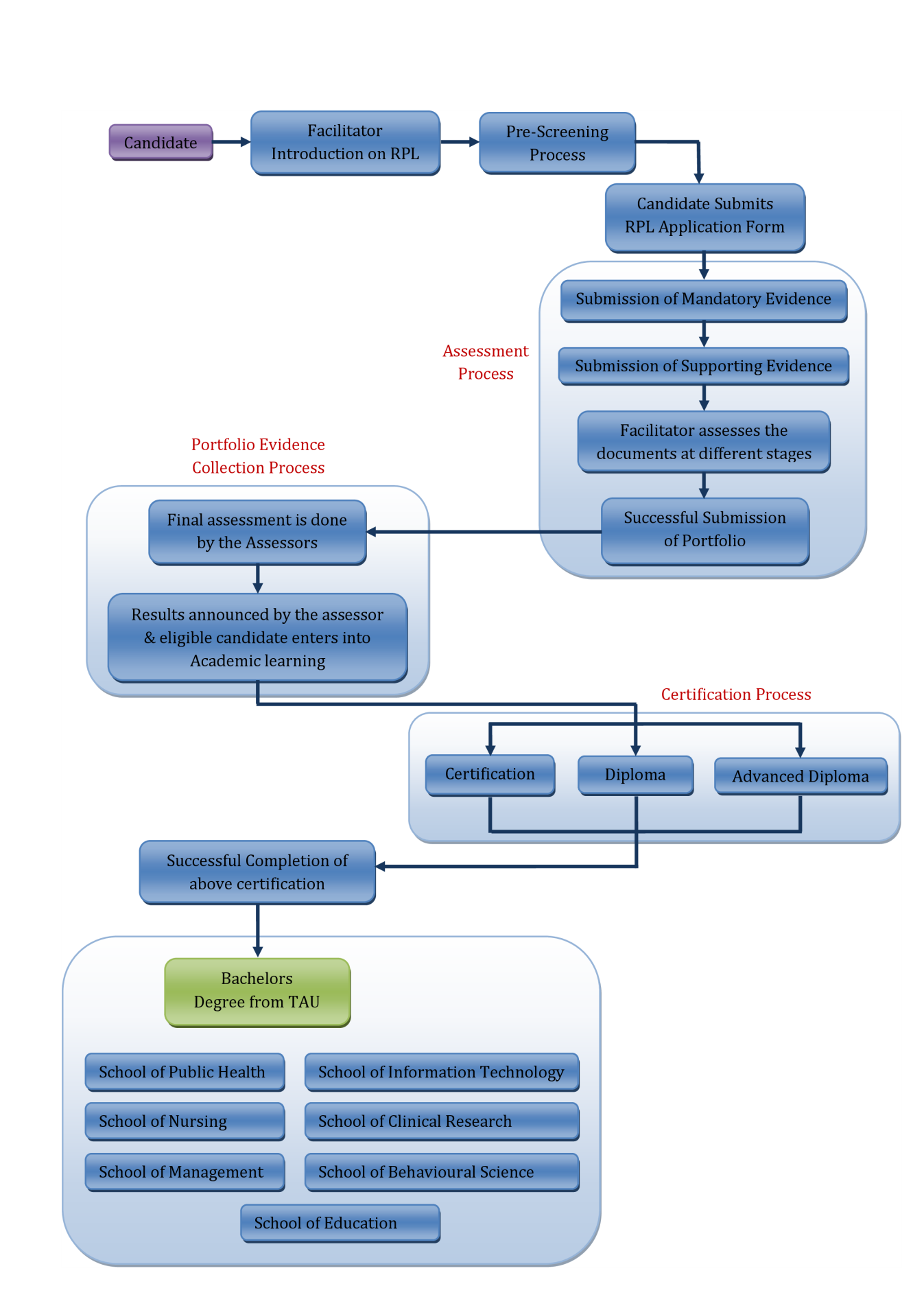

Procedures and processes

RPL undertaken by LabourNet:

- makes use of formative assessment, which draws more attention to identification, and documentation of learning progress and gives feedback to learners;

- uses occupational standards as benchmarks that are accepted by an industry so that workers have an opportunity to get an appropriate employment after the training.

- evaluates the skills of carpenters, masons, plumbers and painters to identify the skills gaps so that it can train the right people for the right roles.

- provides a skills set level, in order to define the right (training) content and hence the instructional design to support it.

Assessment ensures that competences measured are relevant to a specific trade. This is undertaken by a team of industry experts, vocational experts, instructional design experts, content writers, and assessors.

Assessment starts with creation of a question bank by this expert team, who selects questions to be included in the test and arrange them in increasing order of difficulty so that those taking the test may be categorized as unskilled, semi-skilled or skilled. These questions are adapted from curricula and assessments developed in consultation with industry clients of LabourNet’s training programs.

Design and implementation of assessment tests include the following features:

- assessment drives are conducted together with worker registration drives for the LabourNet program as a whole, and are delivered with the support of labor coordinators who assemble workers for assessment;

- assessment is conducted on-site;

- delivery of tests is outsourced to a professional survey team. Evaluation of the tests is conducted centrally at LabourNet’s offices;

- report cards are prepared and mailed/couriered to labor coordinators for distribution to the workers;

- there is no standardized pathway from assessment to training;

- assessments and any follow-up training are currently offered free of charge to workers.

Within the construction industry LabourNet developed assessment tools for four trades (masonry, carpentry, painting and plumbing), taking into account content availability, subject matter availability, number of workers in the pipeline, and location of catchment areas where these workers are found.

Outcomes and ways forward

By 2012 LabourNet had registered 3500 workers of whom 3018 had been assessed; 600 of those assessed had yet to receive their report cards.

The key recommendations by LabourNet for the future are:

- to focus on clear communication about the goals and value of RPL to workers;

- the importance of properly trained assessors and standardized assessment procedures;

- securing the buy-in of stakeholders, particularly employers;

- recruiting and supporting learners;

- guaranteeing quality;

- designing suitable assessment environments;

- managing time and resource constraints;

- addressing issues of esteem with respect to formal training;

- the inherent value of recognition for its boost to workers’ self-esteem and sense of ownership of their work.

Introducing a national policy on RPL along with fully implementing the national qualifications framework would be a valuable part of an overall approach to improve access to training for Indian people; particularly those who may in the past have been excluded from education for whatever reason.

References

City Guilds Manipal Global. 2012. Credit Where Credit’s Due: Experiences with the Recognition of Prior Learning and Insights for India: A Case Study. Bangalore, City Guilds Manipal Global.

Source: UNESCO UIL